N’allez Pas Trop Vite” Marcel Proust, 1919

I’m sleepy, just waking up, still in bed. Guy has brought me a cup of tea and I’m listening as he tells me about the conversations he’s having with his mom. They’re reading Proust together. He’s trying to help jog her failing memory after surgery. I knew Sonia loved to read the French novelist, if one can call what he writes novels. Just last month, when we stayed in Sonia’s downstairs guestroom in her masterfully fenestrated Georgian house in Winchester, we found three different editions of every volume Proust wrote. At this point Guy is three weeks into their discussions, and of course, we are now talking about Proust.

I have things to do, I have to get up, I have a book to write about my latest project—searching for paradise—but Proust has a tendency to slow everything down. Guy starts reading a passage from “How Proust Can Change Your Life,” a valiant attempt at interpreting the author by Alain de Botton—which proclaims under the title, Not A Novel. De Botton is recounting an exchange between Proust and an American Diplomat in Paris at the end of the Great War. The American, Harold Nicolson, writes in his memoir, “Proust is white, unshaven, grubby, slip-faced,” and goes on to tell of his conversation with him. Nicolson is asked about the peace meetings he’s been attending, telling Proust, “Well, we generally meet at 10:00, there are secretaries behind…” These words elicit from the grubby Frenchman a barrage of complaints and demands for more detail, “Mais non, recommencez. Vous prenez la voiture de la Delegation. Vous descendez au Quai d’Orsay. Vous montez l’escalier. Vous entrez dans la Salle. Et alors? …Mais precisez, mon cher monsieur, n’allez pas trop vite.” Proust’s entreaties are to slow down, take your time, tell me about the car you came in, the stairs you walked up. Don’t go so fast.

As my mind wonders I hear Guy say, “I’ve been finding if you do slow down and start by recalling details, things start to come back to you. I’ve been remembering things about traveling across the Sahara I had forgotten.” Long ago Guy told me about hitchhiking from England to West Africa and back. It was 1974 and he would turn 20 later that year. He still has the old Michelin map of Africa. He pulls it off a cluttered shelf in his office now and then and unfolds it, and one can see the route he took in demarcated jagged lines and circles where he stayed. Over the years I’ve heard only snippets of this adventure. I know he stayed in Nigeria for two months and almost got a job teaching English. On his way back someone stole his boots one night when he was sleeping, even though he buried them in the sand. By then he had run out of money and had only flip-flops to wear as he pushed north through Franco’s Spain during the winter. One of the most surprising things he ever told me was that some years later, he threw away the journal he wrote while he was traveling. “Wait! What!? Why?” I shrieked. To this day he has never come up with an adequate explanation.

Now he starts telling the story.

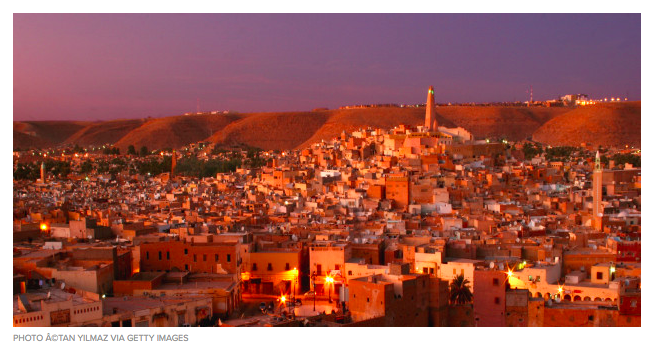

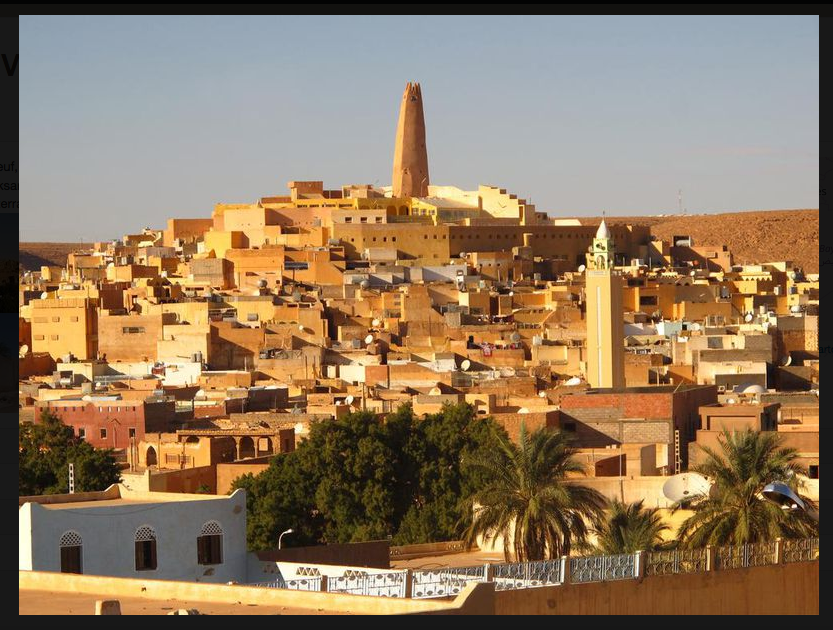

“I left Algiers and traveled south across the Atlas mountains by bus—at night in a lightning storm. At daybreak we came down from the mountains onto the desert floor, and 200 kilometers or so later we arrived at Ghardaia. I was looking around the town that lay in a depression in the desert.” He gestures by dipping his hand in the air saying. “A soft valley. The houses and buildings were made of mud and everything was a faded white.” He tells me, “I hadn’t been there long when I met 3 young Europeans traveling together.”

Once again my mind wonders, this time to Tony Judt, and his book The Memory Chalet. Judt, the wonderful historian and political essayist, wrote the book in his last days while suffering from ALS. Paralyzed and unable physically to write, we would lay in bed and search through what he called his Memory Chalet. By walking through the doors and entering the ordered rooms of a Swiss Chalet, now in his mind, he would retrieve his early experiences. In the morning Judt would recount the reconstructed memories to the young woman writing them down. I think to myself, Guy’s been searching through his Memory Kasbah.

“Who were these people you met there?” I ask him.

“Who were these people you met there?” I ask him.

“They were English and Dutch and had been traveling together for a while,” he says. “They knew each other pretty well. I can’t remember how we met, but we started doing things together. They spoke French pretty well and had gotten to know a merchant in the town who sold local wares, things like baskets and sandals, rugs made of camel hair, and dates, of course. One night the merchant invited us to his home for dinner,” he says, then pauses.

I ask, “What happened?”

Looking thoughtful, he tells me, “We found ourselves in a walled garden where palm trees grew. We ate outside on a low table, and the man brought out platters of couscous and little dishes of dates and nuts. It was the first time I ever ate couscous.” He paused again before saying, “We were in the middle of the desert in the middle of this town sitting in a walled-garden eating couscous under the moon shadows of date palms,” he repeats with amazement. “One of the fellows I was with was so moved, as I was, that he looked around marveling, swept his arm across the setting, and said to our host, ‘C’est un Paradis.’”

As he speaks it strikes me that Guy’s words sound as if they’re coming off the page of a travel journal, a record of his thoughts and impressions. Yet these are the reflections of a different kind of journey, one to the past, to the deep and pleasant moonlit night in a Saharan oasis located now firmly in his memory. Inspired by Proust, he found Paradise hiding there in the past. He walked through the once faded alley ways of his own magical Kasbah, and pieced together the fragments of time. And now he was able to return to that place, as if he had taken a little taste of the madeleine that transported Proust back to the sensations of his childhood home in Combray.

He says, “After stressing out getting through France, Spain, Morocco and northern Algeria, it was suddenly OK to slow down.”

I ask him “Why were you rushing so much?”

“I was reading a lot of Kerouac then, and I must have been influenced by his maniacal intensity to just keep going—It’s all about getting to the next place. He pays no attention to anything on the way.” (Ironically, Kerouac’s main character in On the Road is Sal Paradise.)

“But suddenly none of us were in a hurry anymore. I had enough money at that point to stay there for a few more days, so I did. The people were reserved, but they were gentle and friendly too. I also needed to figure out how to cross the desert. After Ghardaia there was no public transport south through the Sahara.”

Since then Ghardaia, Algeria, the town Simon de Beauvoir once described as a Cubist painting, has been designated a United Nations World Heritage Site. The inhabitants of the city that Guy moved among so many years ago are known as the Mzab people who fled to Ghardaia in the 10th century to escape persecution in the north. He never again saw the three young travelers he met there.

We look up the word Paradise and though it is attributed first to middle French, then lower Latin then to Greek, if you go back far enough you find the word’s origins to be Avestan, one of the two ancient languages of old Iranian, (the language that documents the sacred books of Zoroastrianism). The meaning of Paradise in Persian refers specifically to a walled garden.

Guy says, “I’ll have to tell my mom that Proust is helping me remember things I had forgotten about my trip to Africa.” Guy told me his mom never understood why he decided to hitchhike to Africa, especially since most of his friends were going to India to visit Ashrams and find enlightenment, on a journey his Dad used to call the hash trail to the east. I tell Guy, “You crossed the Sahara and found Paradise instead.”