Elizabeth Bourgine talks to Robin Andersen about creating the role of Catherine Bordey on Death in Paradise

Elizabeth Bourgine walks into Le Select café on the Boulevard du Montparnasse with the same air of confidence and warmth that she brings to her character Catherine Bordey, on the BBC TV series Death in Paradise. I’m already here when I see her walk through the door. She said Le Select, close to where we were staying near the Luxemburg Gardens, was a “typical French café,” so when I saw the long line of broad windows open onto a wide street I was surprised. I had expected something smaller, darker, maybe described as cozy. She greets the shy-looking man at the door, lingering a little as they speak. When she turns to me I cock my head and give a little wave. She’s wearing a knee-length black pencil dress with broad horizontal stripes at the waist, patterned black tights and a leather jacket that broadened her shoulders. Waves of chocolate brown hair touch the top of the jacket. She couldn’t look more different from Catherine, but the way she moves is unmistakable. She occupies the space with her presence like a theater actor does on the stage.

I am sitting at a small round two-top in a surprisingly comfortable French wicker chair. I’d been watching the young tattooed backpackers passing glamorous Parisians on the sidewalk. She gives me the same warm greeting she gave the shy man at the door before she sits down and orders a coffee. It was about 10:30 on a cool Friday morning in Paris when we start talking.

We arrived in Paris the afternoon before aboard the Euro Star—the “chunnel” train that speeds under the English channel from London to Paris. When we started our journey my interview with Elizabeth was not yet finalized, but it didn’t matter. It was Thanksgiving week and we were on an adventure. Neither Guy nor I had been to Paris for more than 20 years, so we visited his mom in Winchester and headed for the City of Light.

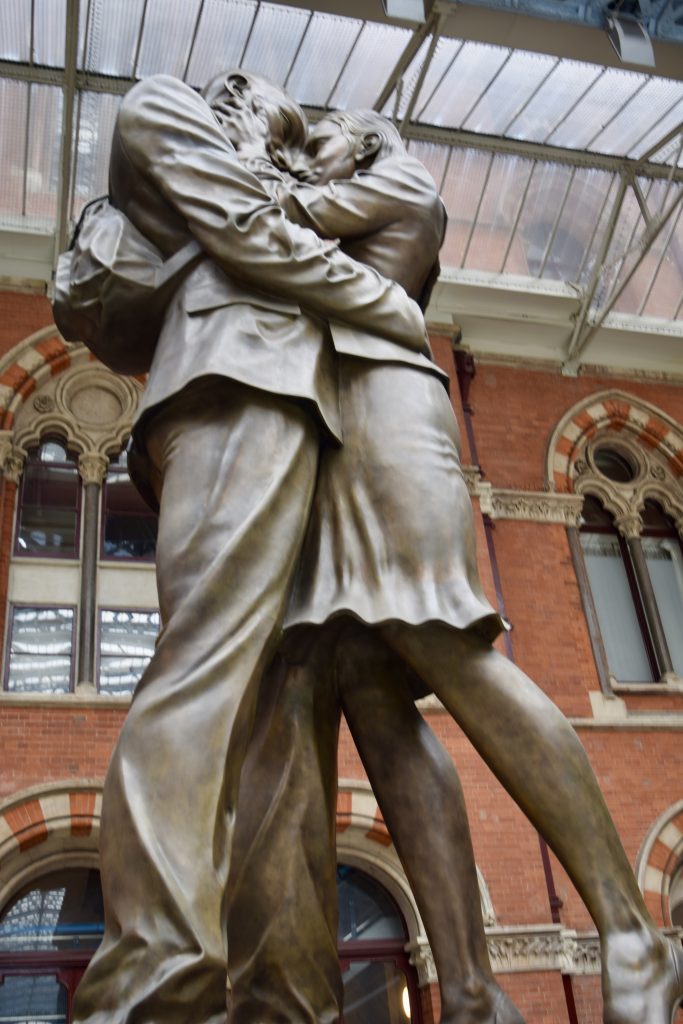

We rolled our bags down the uneven path to the Winchester train station as the low winter sun reached out between narrow trees. Arriving at Waterloo station on a fast commuter train, I dashed to a power outlet to text Elizabeth. My message was brief and unassuming; would we still be able to meet this weekend? That done, we climbed into the back of a London taxi for the 20 minute ride to St. Pancras Station, where we were awed by the grandeur of the old sprawling brick building that seemed to go on forever. Newly renovated, the arched colonnades grabbed our attention with bright white syncopated bricks curved over the warm burnt reds of the walls. We hiked around the perimeter until we found the entrance. Once inside we stood still, and gazed up at a huge towering bronze sculpture of a couple, their feet above our heads.

Standing in an intimate embrace, the two seemed to be dancing, but as we circled around them, our heads tilted up in an awkward twist, we saw that they stood still, foreheads touching–her arm wrapped tightly around his shoulder, the other caressing his face. The British sculptor Paul Day, had originally proposed that the couple be kissing. But here they stood amidst the often frantic speed of international train travel, quietly; an aesthetic enigma in a lover’s embrace. “The Meeting Place” is thought to be a self-portrait, depicting Day and his half-French wife, Catherine, and the Anglo-French bond that they embody. We were off to meet another artist who connects the two cultures. Bourgine also creates a French-speaking woman named Catherine, this one for British television. From her terrace-bar-over-the-bay in the fictional town of Honoré, so often featured on Death in Paradise, the character of Catherine helps create the magical mise-en-scene that both British and French viewers love to watch on the mythical island of Saint Marie.

Bourgine is saying, “You know Catherine is a free spirit,” as she holds her head up, straightens her torso and pulls one arm closer to her body. So much of what Bourgine brings to the screen is physical. Catherine moves through the television space, greeting guests and often walking across the road between the bar and the terrace. She commands attention.

“Catherine is a proud woman, independent and strong. You know she is not just bringing beers,” Elizabeth explains. When she auditioned in late December 2010 for the role of Catherine, she knew they wanted someone over 50, and that was about it, except that she would also be someone’s mother. Then in February in the early hours of a Saturday morning, she answered the phone to hear she had been cast for the part. By Tuesday she was on a plane to Guadeloupe. She read two scripts crossing the Atlantic and found that Catherine also owned a bar. Unlike so much of American television, where main character backgrounds are pretty much drawn out in the program “bible,” Bourgine knew little else about the woman she would play. She would have to build the character little by little. “She’s running a bar you know, so she knows how to be nice to people, but she’s a single woman and still attractive. How many single women of her age do we see?” I give a little nod of appreciation to that insight. “So I thought, I will have to make her a social warrior,” she says with determination. “She’s a mother yes, but she’s still attractive and sexy. She’s unattached and she can be funny. She’s not just a mother.

Arranging this interview with Elizabeth began four months earlier at the end of a long night of shooting on the set of Catherine’s Bar. The location for the bar is the terrace of Le Madras, a café in the village of Deshaies on the French island of Guadeloupe. Filming the end of the last episode of Season 8, Elizabeth walked across the road with a tray of drinks through a warm drizzling rain more times than I could count. I was worn out just watching.

The scene was shot on a rainy night in Deshaies, Guadeloupe

As the crew wrapped up, I went into Le Madras where Elizabeth was gathering her things, and asked, “I know it’s really late and we’re all tired, but could I talk to you sometime in the next few days?” Amazingly, she did not brush me off or get annoyed, which would have been a reasonable response. Instead she said, “I’m sorry, but I’m flying back to Paris in the morning.” I paused only a moment before responding, “I need a really good reason to come to Paris, I haven’t been there for ages. Would that work?” She gave a tentative, but friendly, “Yes, why not?” Delighted, I tell her I’ll message her on Twitter. And so the plan to meet in Paris was drawn with a social media back and forth to determine which dates would work for both of us. When I suggested Thanksgiving weekend, and she said she’d be in town, but we never confirmed which day and time.

Waiting in the downstairs departure lounge at St. Pancras, a state-of-the-art area with warm wooden floors and glass walls, I was taking a last gulp of latte after the speaker announced it was time to board, when my phone pinged at me. As I snuggled into the comfortable seat I thought of the questions I’d ask her. The interview was set; Elizabeth would be available the following morning, and we were to meet at a café close to both of us, and across the street from the American bar, La Coupole, where it is said that in the 1920s, guests were served lamb curry by Indian waiters in full sumptuous costumes. Today it’s more famous for its fancy cocktails.

I am asking Elizabeth about Catherine’s relationship with her daughter, Detective Sargent Camille Bordey, played by Sara Martins on the show. Their interactions cover some of the usual mother-daughter television conventions—Catherine would be happier if Camille were married, for example. Helping her find a marriageable man, Catherine arranges the perennial date, which invariably turns into an awkward affair.

But there are also more challenging issues raised between them. The mother-daughter storyline is a significant thread In Season 3, episode 5, titled Political Suicide, and the issue that it raises stands out for its universal theme and emotional complexity.

The sequences are masterfully acted by Bourgine and Martins, and the other cast members.

Through the course of an investigation, Camille discovers a mysterious stranger in town who shows up at the scene of a crime. He is a suspect and as it turns out, he is also her father. She hasn’t seen him since she was six. The versatile and intense Clarke Peters—one of David Simon and Eric Overmyer’s favorite actors, best known for his roles as detective Lester Freamon on The Wire, and the proud Big Chief Albert Lambreaux on Treme—is cast as Camille’s father, Marlon Croft. He plays an islander from St Lucia with a relaxed air, though as a negligent father he brings a sense of defensiveness to the role.

Camille is hostile to Marlon, having always been told by Catherine that he left them when Camille was very young. This is the story everybody has heard from Catherine, as Police Officer Duane Myers (Danny John Jules) explains to D.I. Humphrey Goodman at the station, “He walked out on her and her mother when she was a kid.”

After Marlon is ruled out as a suspect, Camille goes back to confront him. She tells him, “I know what you’re like.”

“You’ve not seen me for 25 years, and you know exactly what I’m like?” he responds.

“I’ve heard the stories,” she says.

“From your mother you mean?”

As the scene plays out Marlon tells her, ”Me being out of your life? I was only doing what I was told. What she [Catherine] asked of me.”

Camille is devastated by what Marlon has said. She asks Catherine if it’s true, but leaves little time for her mother to respond. Camille leaves the bar distraught, and Humphrey follows her out. When he catches up to her she tells him, on the verge of tears, “She has lied to me my entire life.”

The resolution to these conflicting stories takes place when Catherine comes to the Police Station. She begins by saying, “I’m just asking for a chance to explain.”

Elizabeth Bourgine plays the scene with quiet but intense emotion. She is at once dignified and vulnerable. But what makes the acting so powerful is the precision she brings to the pacing. She stands in the sun, the camera in sharp focus. Sara Martins, with her back to the sun, takes the more gentle, backlit position. As Camille listens, Catherine tells her what happened when they lived with Marlon on St Lucia.

“One morning he took you to the beach. She pauses and says with a measure of indignation, “By nightfall he still hadn’t come back.“ Then, “I was going frantic!”

“Eventually, I found you, on your own. Marlon was in a bar nearby, playing cards. He has forgotten he had you with him.” Catherine pulls herself up and reveals to Camille, “It was the day I realized he couldn’t be a father to you. So I brought you back home, to Saint Marie. It was what I thought was best for you.”

Later back at the bar, toward the end of the episode, Camille tells Catherine, “And you’ve done the best for me every day of my life.”

This storyline is well written, acted with eloquence and nicely woven through the episode. As all of the characters interact with Camille, the bonds that tie them are strengthened. It allows Sara Martins to deliver a moving portrayal of personal anguish and resolution. And yet I find myself wanting to see some interaction between Marlon and Catherine. After all, it’s their story too. Years have passed when Catherine’s estranged husband comes back to Saint Marie. How might a meeting between them play out? My dramatic imagination ponders two such formidable actors together on screen. I ask Elizabeth if she met Clarke Peters when he was in Guadeloupe to film the show. She tells me, “No I would have like to meet him.”

Over eight years Elizabeth has been involved in helping create a rare television personality, one among a crowded field of diverse main characters, in a cast also filled with well-known British guest stars on every episode. Probably the greatest challenge came when her fictional daughter left the island. When Camille gets on the boat to take her dream job in Paris, a good portion of Catherine’s identity goes with her. I ask Elizabeth what she thought when Sara left the show. She tells me, “I thought, why keep the mother?” Elizabeth offered the producers an idea. “So now Catherine can be more a part of the social life” of Honoré. “She is without a daughter, why can’t she be the mayor?” Indeed, Catherine does becomes the Mayor of Honoré, a position that sometimes places her more toward the center of storylines, even though the subplots remain outside of the main thread of the crime puzzle, so far.

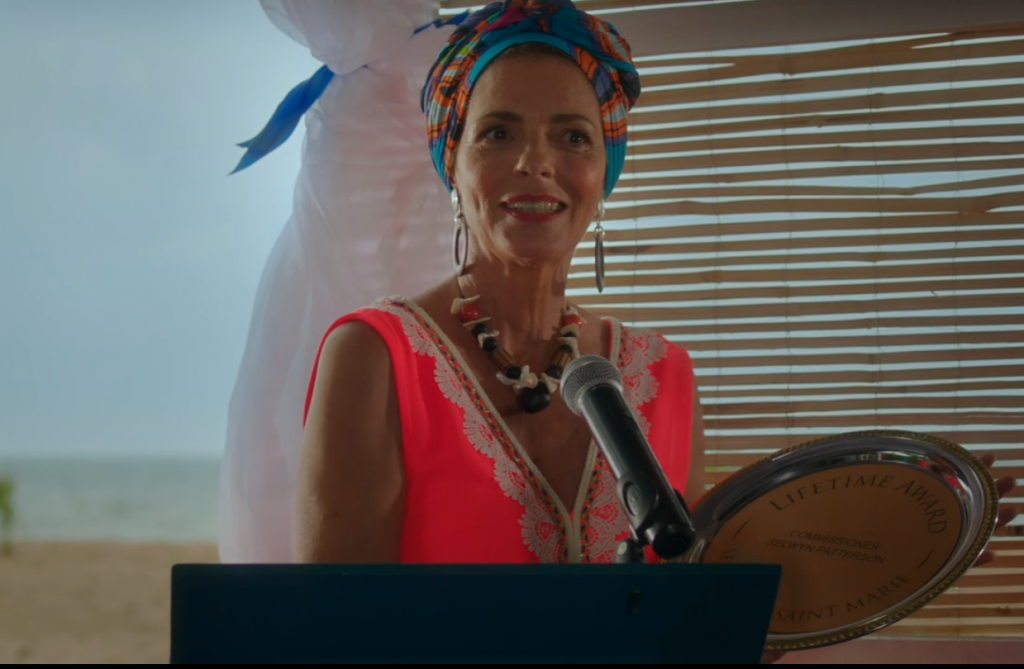

One of my favorite episode is in Season 7, when Mayor Catherine is coaching Jack Mooney, the third Detective Inspector to appear on the show, helping him write a speech about the commissioner. The enigmatic Commissioner, Selwyn Patterson played with quiet panache by Trinidadian-born British actor Don Warrington, is to be given a significant island prize, and Jack must say something about Selwyn before he receives the award. Much of the episode actually revolves around this story thread, and it includes a sequence where Catherine gives Jack advice about Selwyn’s introduction. She tells Jack, “When I became mayor I was terrified of speaking in public. But I realized there are only two things to remember.”

“And what are they?” he asks.

“Keep it short.”

And the second thing?”

“Keep it short”

Jack says flippantly, commissioner, you’re a great fellow here’s your award.

Catherine tilts her head to the left, purses her lips, the corners of her mouth slightly up, flashes her eyes and murmurs, “ Hum-hum.”

Later we are treated to Catherine at a lectern introducing Jack in her official capacity as Mayor.

On a program that covers quite a bit ground in a short amount of time, scenes move quickly. Catherine has less airtime than any of the other main characters, forcing Bourgine to make each appearance memorable no matter how brief. She accomplishes this with breathtaking ease.

Catherine’s appearance helps define her character. The costuming helps Bourgine present this rare female TV presence. “I go to London in the spring with the costume designer, and we visit flea markets and consignments stores,” she tells me. On a shoe-string budget, Elizabeth ties the fragments of cloth and adornment she finds in London with things she has acquired in Parise, mixing different colors, elements and styles to create the unique look that Catherine brings to global screens. African scarves are mixed with dresses of compatible print and accented with beads, arm bracelets and dangling earrings. Catherine is portrayed as a Saint Marie native, and with her accent and Mediterranean complexion, together with her style, she represents a multicultural character of imagined descent, adding another layer of global citizenship to the program and its setting.

Catherine represents a unique portrayal of a mature, single woman who is confident, attractive and wise, untroubled by her lack of attachment to a man. She is an independent business woman, now a politician, conferring upon her additional attributes that diverge from the usual television tropes that define women “of a certain age.” Her character is a vision of grace and a font of wisdom, and the French actress sitting across from me has had no small part in this creation.

Through the tall windows of Le Select, I see Guy on the sidewalk outside. He’s back from his wanderings through the neighborhood, and I motion to him to come in. We both sit and talk with Elizabeth for another 15 minutes, reluctant to end the conversation. We finally stand and say goodbye with a hand-shake and two kisses in the French style, one on each cheek.

Check in next week for more about the show and the village of Deshaies, Guadeloupe, were Death in Paradise is filmed.