After hearing for so long about Maho Bay, I’m finally visiting the eco-tent camp during what seems to be its last couple of months. Opened in 1976 by Stanley Selengut, it has served since the first nails were hammered into the wooden boardwalks, tents and gathering areas, as an eco-lodge innovation that it is now a classic icon of sustainable travel. We didn’t venture far from camp our first day, instead we decided to get acquainted with the place. The northeastern storm had followed us down from New York, and Jason at activities, advised us that the swell it brought with it would affect conditions at Little Maho Bay more than Big Maho. Continue reading Visiting the Eco-tents at Maho Bay

After hearing for so long about Maho Bay, I’m finally visiting the eco-tent camp during what seems to be its last couple of months. Opened in 1976 by Stanley Selengut, it has served since the first nails were hammered into the wooden boardwalks, tents and gathering areas, as an eco-lodge innovation that it is now a classic icon of sustainable travel. We didn’t venture far from camp our first day, instead we decided to get acquainted with the place. The northeastern storm had followed us down from New York, and Jason at activities, advised us that the swell it brought with it would affect conditions at Little Maho Bay more than Big Maho. Continue reading Visiting the Eco-tents at Maho Bay

Fighting for Wild Aruba

From the edge of the deck the sand travels away from the light in wavy peaks and shadows. Trunks of palms wrapped in spiral beads of light surround the deck. They sway and rustle in the wind. A few feet away the sand meets the darkness and radiates upward through a cloudless night sky. The leeward side of the Caribbean sea murmurs as melodies float from the bar at the other end of the deck. Large round posts support a thatched roof. They are wrapped with ties that secure decorative linen curtains. Huge garden pots sprout tropical greenery. No cell phones ring. Sounds of soft laughter on the wind are punctuated by clinking drinks returning to the glass tabletops.

A woman walks off the deck and down the wooden stairs into the sand making new patterns in the expanse of creamy grains. She moves closer to the water toward a  secluded palapa where two people sit at a table dressed in tropical décor. The white linen curtains attached to these posts are pulled across the openings, creating a romantic enclosure. The secluded fantasy presents a dreamy scene where nature and civility, paradise and hospitality meet in harmonious accommodation. Continue reading Fighting for Wild Aruba

secluded palapa where two people sit at a table dressed in tropical décor. The white linen curtains attached to these posts are pulled across the openings, creating a romantic enclosure. The secluded fantasy presents a dreamy scene where nature and civility, paradise and hospitality meet in harmonious accommodation. Continue reading Fighting for Wild Aruba

Learning to Fly at the End of the World: Travels Down the Yucatan Peninsula

A second huge palm frond hits my left shoulder, catching a little of my face this time. It smacks the woman behind me dead on. She squeals and leans down to her daughter, placing the girl’s little hand on the offended cheek. The salsa pounds and the colored flashing lights pulsate to the beat of the blaring music. The top of the bus sways as we follow the curve on this part of the Bahia Boulevard, a beachfront drive that snakes down the peninsula for another 20 kilometers. I stick my head out over the bus’s narrow railing to check for another frond. The shallow green water of the bay spreads into the darkness on the right, mangroves and sea grapes blocking any light from the cafes and bars that might find its way to the beach. A wind gust catches another great arm waving in the center divide and the frond reaches down. I duck.

I am on assignment writing about the port destinations on the Yucatan Peninsula. My guides Dennerik and Harley took the night off. We’ll start again early in the morning. They want me to see the museum, the zoo, the telescope and other attractions that might draw tourists. But this ride is not on my itinerary. No cruise passengers will ever linger this far from the port this late at night. I can’t help them with the bus; tell them when it runs or how much it costs. Their ship will be guided away from the pier well before the first bus ever leaves the plaza. They’ll never be slapped by the fronds.

I am on assignment writing about the port destinations on the Yucatan Peninsula. My guides Dennerik and Harley took the night off. We’ll start again early in the morning. They want me to see the museum, the zoo, the telescope and other attractions that might draw tourists. But this ride is not on my itinerary. No cruise passengers will ever linger this far from the port this late at night. I can’t help them with the bus; tell them when it runs or how much it costs. Their ship will be guided away from the pier well before the first bus ever leaves the plaza. They’ll never be slapped by the fronds.

The bus turns and we fly slowly around the palm trees and I head back the other way. Now the restaurants are on the right and red light pours out from under El Diablito’s thatched roof promising grilled steaks and karaoke. People dash in front of the hulking vehicle on their way to the beachfront, and as the driver brakes we jerk forward.

Back at the plaza where our ride began, some of the kids are still driving their miniature SUVs over the smooth stonework — at least they are electric. The older muchachos, often with the help of a parent, fly their fantastical papalotes. The sky-born kites catch some of the light from below; their faces and shapes slide in and out of view. Green eyes peer down from a wing-shaped kite giving flight to a jaguar, the dark face surveying the plaza below. It is almost midnight and head back to my hotel room.

In the morning we’ll head straight for the Museum of Mayan Culture. I’ve seen the

archeological sites of Chacchoben and Kohunlich, and they are stunning in their beauty and grandeur, though they are proportioned to a human scale, so unlike Ramses I and II. Their curved corners, passageways and windowed walls direct the light into shafts,

archeological sites of Chacchoben and Kohunlich, and they are stunning in their beauty and grandeur, though they are proportioned to a human scale, so unlike Ramses I and II. Their curved corners, passageways and windowed walls direct the light into shafts,

revealing sky in unexpected flashes. Only released from the jungle in 1999, I want to know more. I had no guide the morning I made the visit to Kohunlich. Javier, one of my companions for the first leg of the trip, had to meet other European guests arriving back at the lodge, so I’d seen it on my own. Javier whisked me into the Jeep early so we could be at the gates when they opened at 8am. An hour later, he told me, I would be picked up by 2 men driving a red Ford Fiesta with a tourism logo on the side. As we ambled toward the entrance to Kohunlich the sounds of the jungle jumped out with a roar, then another roar. Javier lowered his hand, spreading his fingers out flat, cocking his head as he’d done on our hike the day before and said, “Listen. A jaguar.” My eyes widened; we heard it again, this time followed by a series of classic puckered-mouth monkey sounds. It was a howler. We looked at each other and laughed, and I walked alone through the gate. I was the only one there.

In the excitement of seeing one structure after another, one more beautiful than the next I snapped shots furiously. Some trees still claimed the stones, growing out of stairs and  inside walls. I tromped up steps, saw better angles, ways to frame light and compose palm trees against bright, blue skies and stone walls. Pausing on the top of one temple, the quite stoicism of the place halted me. The digital SLR moved away from my face, my knees bent, lowering me to a stone buttress. The buildings moved closer and became more silent, and the grassy areas that separated them, more lush. Color, dimension and silence now engulfed the place. I marveled and saw my lanky cousin Jay, forever joking and bending his quirky head down to reach my face, pausing before delivering a punch line. My sister’s email told me that the man who married my aunt’s daughter Donna, cousin Jay, became suddenly ill and had died unexpectedly. There would be no service in California. I left from New York on this trip only days after I opened the email, and in the rush had no time to remember Jay. I now imagined him soaring overhead, looking down with approval on the chiseled structures that endured.

inside walls. I tromped up steps, saw better angles, ways to frame light and compose palm trees against bright, blue skies and stone walls. Pausing on the top of one temple, the quite stoicism of the place halted me. The digital SLR moved away from my face, my knees bent, lowering me to a stone buttress. The buildings moved closer and became more silent, and the grassy areas that separated them, more lush. Color, dimension and silence now engulfed the place. I marveled and saw my lanky cousin Jay, forever joking and bending his quirky head down to reach my face, pausing before delivering a punch line. My sister’s email told me that the man who married my aunt’s daughter Donna, cousin Jay, became suddenly ill and had died unexpectedly. There would be no service in California. I left from New York on this trip only days after I opened the email, and in the rush had no time to remember Jay. I now imagined him soaring overhead, looking down with approval on the chiseled structures that endured.

Sitting in front of the visitor’s center, I saw the red Ford Fiesta swing around the parking lot kicking up dust, and stop a few feet away. I started toward them as they unpacked themselves from the little red car. Dennerik was young and serious, and Harley was Mayan with a face more cheerful than the ones carved in stone that looked just like him. We piled back into the car quickly as I waved and said gracious to the boy I had been grilling about hours of operation, the cost of the ticket and if they had a website.

For the last 2 days Harley’s been driving and Dennerik’s been sitting in the middle of the back seat, leaning forward pointing things out and taking breaks to text updates of our progress to the jefe – the big boss in the office. From Dennerik’s description I think of the jefe as a dark brooding force, forever worried if they’re showing me the perfect places and the most alluring attractions that will make this remote place irresistible to tourists. When we pulled into this little city on the bay I was deposited at the Holiday Inn, the nicest accommodation they assured me. Dennerik apologetically reminded me not to be late for my scheduled dinner with the tourism official.

At dinner that night with my amiable host, I first saw the bus they call el carro. Chatting with the head of tourism for the state about all the things to see and do in Quintana Roo, our conversation halted every twenty minutes as the bus tumbled past the outdoor patio, lighting up the street in a musical explosion and peals of laughter. I paused to stare at the sight of this fun box on wheels as it made its way up the boulevard. Following its progress up the road, I noticed a park on the north side of the street where children were skating up and down the sidewalk under the lamplight. They made a circle around a large statue of a mother and child. “What does the monument commemorate,” I asked. “Victims of a terrible hurricane of 1935. This is why there are still no residential houses along the beach. So many were killed, they rebuilt back, away from the shore,” he waved into the darkness.

Up the road beyond the statue and another open plaza, a large box store loomed. I wanted to ask my host why a Wal-Mart would appear on beach-front property, but I didn’t want to spoil the conversation or a journey that was beginning to seem very far away from the cement of life as we know it.

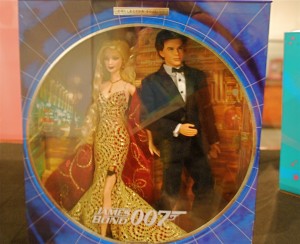

Dennerik and Harley are early as promised and we pile into the Fiesta taking are usual seats and head off for the Museum. Strolling around the interior spaces of the museum grounds, they are still apologizing. When we arrived the exhibit of the Maya was  surprisingly closed. But there are other things to see. Papier mâché sculptures, the work of local grade schoolers, populate the walkways of the interior courtyard of the museum. The fanciful creatures sit atop clean white columns, making their bright colors more dramatic by contrast. Dennerik reads aloud from a card under a stocky green turtle sprouting big blue wings. “I hope I can fly,” he translates from Spanish. I ponder a minute and ask, “Could it be, ‘I wish I could fly?” “Yes,” he says, “that’s it.” Harley comes out of an open doorway wearing a bemused face saying excitedly, “You have to see this.” We pass through the door and see a room filled with Barbie Dolls.

surprisingly closed. But there are other things to see. Papier mâché sculptures, the work of local grade schoolers, populate the walkways of the interior courtyard of the museum. The fanciful creatures sit atop clean white columns, making their bright colors more dramatic by contrast. Dennerik reads aloud from a card under a stocky green turtle sprouting big blue wings. “I hope I can fly,” he translates from Spanish. I ponder a minute and ask, “Could it be, ‘I wish I could fly?” “Yes,” he says, “that’s it.” Harley comes out of an open doorway wearing a bemused face saying excitedly, “You have to see this.” We pass through the door and see a room filled with Barbie Dolls.

The dolls stand still and silent under their protective Plexiglas cases. All kinds of Barbies clustered inside, Barbie straddling a Pink horse, balancing forward, face eager; ballerina  Barbie, already on tip toes in a pink tutu; Barbie holding a tennis racket aloft, one foot lifted in frozen expectation. Barbie and Ken on the beach wearing sunglasses and bathing suits, surrounded by supine mermaid Barbies, unable to stand on their pink, purple and turquoise tails.

Barbie, already on tip toes in a pink tutu; Barbie holding a tennis racket aloft, one foot lifted in frozen expectation. Barbie and Ken on the beach wearing sunglasses and bathing suits, surrounded by supine mermaid Barbies, unable to stand on their pink, purple and turquoise tails.

In another case astronaut Barbie waves out of her space helmet, and senorita Barbie wears a pink faux sombrero with a ruffled pastel skirt. Horses in western saddles, their impossibly thick, braided manes reached to Barbie’s feet. They are tied with pink bows.

In a momentary reverie, I imagine a “travel” Barbie and snicker at the thought of her standing next to a steamer trunk adorned with Victorian stickers, in a safari outfit. But, I wonder, could Barbie ever escape her sealed geography, her own world where the rules of pink capture and restructure everything in its gaze? I look at the next case and see Barbie as a rock band, several of her assembled in front of panels that form a stage painted with reflective shinning stars that headline Rocker’s. Lead-singer Barbie holds a  microphone; another Barbie tries to hold a pink guitar but her tight plastic arms are incapable of clutching the instrument. Barbie band could play on a cruise ship I muse, imagining a big titanic-like replica with the Rocker’s on deck entertaining the dining passengers.

microphone; another Barbie tries to hold a pink guitar but her tight plastic arms are incapable of clutching the instrument. Barbie band could play on a cruise ship I muse, imagining a big titanic-like replica with the Rocker’s on deck entertaining the dining passengers.

Then there are Barbies never removed from their collector’s boxes. In the James Bond series, Barbie is wearing a tight gold and red gown as one knee juts out from under the front slit in her skirt. She stands forever still next to 007 Ken.

The children’s mythical creatures welcome us back as we step out into the sunlight and  open spaces of the courtyard. Under the kinetic skins of these denizens of imagination the bright blue, red, purple, yellow and orange bodies seem to squirm playfully in the hot air.

open spaces of the courtyard. Under the kinetic skins of these denizens of imagination the bright blue, red, purple, yellow and orange bodies seem to squirm playfully in the hot air.

“We’ve got to get you down to the port at Mahahual,” Dennerik says early the next morning. “Cesar will meet us at noon. He will have the port manager there, and some other personnel you can talk to. We’ll have to leave right after the zoo.” The zoo is nicely designed. We follow winding paths through tropical foliage and find brightly colored, tropical birds in the aviary. We linger sadly as the zoo-keeper tells us that the petite toucan  he is offering fruit is already virtually extinct, with less than 2000 birds left in the wild. I’m surprised to know that the zoo partners with international conservation programs and is affiliated with the older, better-known Belize Zoo. Wobbling across a rope bridge, a child’s attraction, I almost fall into the water. Harley gasps. We head south.

he is offering fruit is already virtually extinct, with less than 2000 birds left in the wild. I’m surprised to know that the zoo partners with international conservation programs and is affiliated with the older, better-known Belize Zoo. Wobbling across a rope bridge, a child’s attraction, I almost fall into the water. Harley gasps. We head south.

I’m looking forward to seeing Cesar again. He had driven me down the peninsula when I got back to the mainland from Cozumel. Waiting for me outside the extravagant eco-resort on the Riviera Maya, I saw his rigid stance close to the SUV when I came out, “You don’t look happy,” I observed. He lifted the dark glasses and his green eyes flashed, “Let’s get out of here,” he said opening the door. “I told them, and you told them I was coming, and they still did not tell the guard to let me in. I don’t know who these people are, but there not from this state.”

“It’s a Spanish construction firm using Canadian money,” I tell him. “They blasted a canal in the limestone so they could take guests on a boat ride around the perimeter. They call it a bird habitat.”

Cesar is assembled with bits of humanity from around the globe. Born in the Yucatan, his blood mixes Basque, Italian, Arab, and more, into an intensity that could barely be contained in the truck’s cab. As the tires whined, Cesar’s energy shot through the interior and bugs piled up on the windshield outside. The ride down the peninsula was a short course on the complicated lives of cruise ships. He was an excellent teacher detailing the port masters, the investors and insurance companies, and of course the cruise lines and passengers themselves. He explained the complications of moving that many people on and off a large boat with international restrictions. “How do you find the cruise passengers,” I asked him. “Are they nice?” I marveled at how trivial that sounded. “Sure, most of them are just trying to have a good time. They mostly get upset when there are kids. The Disney ships can be tough. If the children aren’t happy, nobody’s happy.” His cell-phone interrupted our conversation and he carefully, with exaggerated, slow enunciation, spells out to the listener, “No I did not threaten to sue them. I simply gave them a bill for the cost of the damage done when their ship hit the pier.” Laying the phone down on the seat he told me, “The pilot of a U.S. research vessel banged into my pier in two places, but nobody wants to pay for the damages.”

Cesar is assembled with bits of humanity from around the globe. Born in the Yucatan, his blood mixes Basque, Italian, Arab, and more, into an intensity that could barely be contained in the truck’s cab. As the tires whined, Cesar’s energy shot through the interior and bugs piled up on the windshield outside. The ride down the peninsula was a short course on the complicated lives of cruise ships. He was an excellent teacher detailing the port masters, the investors and insurance companies, and of course the cruise lines and passengers themselves. He explained the complications of moving that many people on and off a large boat with international restrictions. “How do you find the cruise passengers,” I asked him. “Are they nice?” I marveled at how trivial that sounded. “Sure, most of them are just trying to have a good time. They mostly get upset when there are kids. The Disney ships can be tough. If the children aren’t happy, nobody’s happy.” His cell-phone interrupted our conversation and he carefully, with exaggerated, slow enunciation, spells out to the listener, “No I did not threaten to sue them. I simply gave them a bill for the cost of the damage done when their ship hit the pier.” Laying the phone down on the seat he told me, “The pilot of a U.S. research vessel banged into my pier in two places, but nobody wants to pay for the damages.”

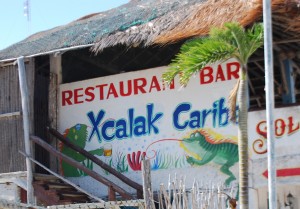

Cesar is the first one we see as we pull into Mahahual. This port on the Costa Maya is a festive new facility, shimmering multi-colors in the Yucatan sunlight at the end of the Peninsula. With no ships or passengers this morning it resembles an empty movie set of a mythical Mexican village. I chat briefly with a manager, snap some shots, ask a cab driver for his prices, and quickly exhaust my need for further information. Sadly, Dennerik and Harley must head back and we promise to meet again sometime. Cesar has some business to do, and I am pleased when he introduces me to Tony and says, “Why don’t you just go where you want and look around the area.” Tony and I head straight down the road chopped out of the jungle toward Belize, and arrive at Xacalak for a late lunch. The  descendants of the Maya and a host of marginal internationalists populate this tiny coastal village. We cruise along the hard-sand shoreline route, stopping to ask several times if anyone has a boat to take us out. Tony makes the arrangements with a group of guys sitting in the shade in language far too fast and abbreviated for my ears. “They need to go pick up some gas and will meet us back at this spot in an hour,” he explains. We find one café open, and the accommodating middle-aged woman follows us from her chair in the sun into the cool, little restaurant with formica tables. “I’ll have the local fish,” I say, and Tony says, “We both will.” After bringing us our drinks, she goes into the kitchen to cook.

descendants of the Maya and a host of marginal internationalists populate this tiny coastal village. We cruise along the hard-sand shoreline route, stopping to ask several times if anyone has a boat to take us out. Tony makes the arrangements with a group of guys sitting in the shade in language far too fast and abbreviated for my ears. “They need to go pick up some gas and will meet us back at this spot in an hour,” he explains. We find one café open, and the accommodating middle-aged woman follows us from her chair in the sun into the cool, little restaurant with formica tables. “I’ll have the local fish,” I say, and Tony says, “We both will.” After bringing us our drinks, she goes into the kitchen to cook.

Beds of seaweed crowd lazily up onto the sand, and extend back, well into the shallow bay waters. Looking out over the ample half-circle, I see the tiny thin thread of white in the distance where the swells meet the coral reef. I changed into a bathing suit after lunch in the restaurant, and I now pull my second leg over the edge and into the boat with a predictable thud. Our captain wraps the waterproof paper bracelets around our wrists that certify our visit to a protected reef. He gives the outboard some gas, stands up and we head for the reef. Tony tells me his mom still lives in LA, but he got deported after getting in trouble a few years ago with his teenage friends. “I’m happy to live here and have a good job,” he says, “and today is a very good day.” I agree as the water zips by. We take a rest from shouting over the motor to watch the changing coastline and the reef moving closer. The boat slows and we search for a place to anchor. The white water topping the swells hitting the reef frames our location on the glassy surface of the shallow water. Tony  searches through his bag and finds no trunks. We each position our masks and fall backwards into the water, Tony in his underwear. A few strokes away from the boat the underwater scene comes to life as shafts of light reaching to the sandy floor dance in a cadence to the movement of the water above. Rock-like coral formations covered in texture, shapes, and purple ferns dot the smooth white bottom, each surrounded by a stunning variety of tropical fish. They dart and sparkle in the moving light of the sun, one after the next, each outcropping inviting more fish with different colors, each claiming my attention and I fly over the quiet underwater landscape and away from the boat and its motor.

searches through his bag and finds no trunks. We each position our masks and fall backwards into the water, Tony in his underwear. A few strokes away from the boat the underwater scene comes to life as shafts of light reaching to the sandy floor dance in a cadence to the movement of the water above. Rock-like coral formations covered in texture, shapes, and purple ferns dot the smooth white bottom, each surrounded by a stunning variety of tropical fish. They dart and sparkle in the moving light of the sun, one after the next, each outcropping inviting more fish with different colors, each claiming my attention and I fly over the quiet underwater landscape and away from the boat and its motor.

Epilogue: Did I forget to tell you? You can board the musical bus that travels the Bahia Boulevard in the town of Chetumal, the capital city of the state of Quintana Roo along the Caribbean coastline of Mexico’s Yucatan Peninsula. If you’ve made it this far this late, your ship has already left the port. But don’t worry; it’s very safe. Nobody locks their car doors along the Bahia drive and the locals are very friendly. There is one bay- front hotel across from the Sam’s Club, with outdoor dining. From there you can go further down the coast to Belize. And by the way, I have it from a reliable source that the Maya did not predict the end of the world. The end of the calendar only gave flight to a new beginning.